Wilderness and its contradictions :

The first thing that should appear as an evidence to anyone are the superficial contradictions between the very use of this notion and the common discourse in our activism about cetacean personhood. In particular :

*Isn't there a contradiction between claiming that cetaceans are non human persons or people and that they are "wild animals" ? Would we call a human "wild animals" or the spaces we live in as "wilderness" ?

*Isn't there a contradiction between relying so much on culture to assess cetaceans as valuable beings which shouldn't be kept captives, and calling them "wild animals" that live "in the wilderness", particularly since "culture" is traditionally opposed to the idea of the "brute" or the "savage" being ?

*Isn't calling them "wild animals" as insulting as calling an indigenous person "savage" because s/he lives in an environments we as westerners deem as "natural" or "backward" ?

The problem, of course, goes well beyond a mere hypocrisy in activists, and the fact that it is so much conserved and deeply rooted in our ways shows that these notions are structurally inherent to our societies and cultures, and must be questioned as such :

Wilderness is a fundamental myth of western societies.

In other words, we were educated in a culture which taught us that there is a fundamental division between two entities called "nature" and "humans". "Nature" or "Wilderness" is systematically imagined in a chaotic or hostile form, generally a floral bloom or a jungle setting. By contrast, humans spaces are imagined as an idealization of the western world : sprawling cities of concrete roads and polluted air, road traffic etc. supposed to "grow against nature" which in itself is understood as trying to grow against human settlement. This idea of a space called "nature", radically separated from a "human space", is as such extremely determined historically, and doesn't reflect well non human realities, but rather both a human and western sociocultural bias over non humans. It in facts well reflects the idea of order and security from a western point of view, determined by technology and the research of material wealth and comfort.

*The idea of a separation between "wilderness" and humans doesn't make sense for several reasons. One is simply that humans are biological and physical entities : they are submitted to the same laws and systems than the "rest" of what we call nature ; we "are" nature in itself. Denying this would be akin to resurrect the old Cartesian spectrum of a radical mind/body division coupled with an exception of man, a anthropocentrist point of view with no real scientific grounds and which is instrumental in legitimating relations of domination over non humans. Another one is that it isn't even sound in the light of ecology : what we call "natural environments" aren't chaotic entities, but well understandable systems with its rules and laws, where species are fit to live in rather than "surviving" in a sort of "soup". As such, the conception of "wild animal" in its more general sense of "an animal living in a space called the wild" seldom makes sense in itself.

But it is mostly the idea that such a divide could roots itself historically and socioculturally that can show the full absurdity of this conception.

*While we believe to be the first, or one of the first, to have started to question the term as for the idea of the "wild animal", the conception of "wilderness" and more largely of "nature" as a non human space was and is still questioned by a plethora of intellectual and researchers. One of the first was the french philosopher and anthropologist Phillipe Descola in his book "Beyond nature and culture". Through his studies of Amazonian indians called the Achuars, he realized that the nature/culture divide isn't universal to all people, that some cultures understand as such non humans as persons, and more importantly that so called "native", "indigenous" or "tribal" cultures made an extensive, active use of their environments, exploiting and domesticating their spaces and lifeforms rather than "surviving" in a "wilderness" or merely harvesting what they passively find (a point we will address later in the text). Descola shows how the Achuars understand what we call "nature" or "wilderness" as a "big garden", where each species fills a specific role and use, which is to be domesticated, shaped and used by man in very specific ways. In other words, what we call and imagine as a "natural space" is a fantasy proper to our urban, agrarian, technologically expanding culture, whereas cultures and societies which evolved in these environment possess another, more accurate, complex understanding and representation of these spaces they indeed occupy and use. What is "chaos" or "wilderness" for us isn't the same for them, as spaces we perceive as "wilderness" will have an order and a logic for these people.

|

| The Achuar people studied by Phillipe Descola understand the jungle around us as "gardens" they tend for rather than as "wilderness" ; the way the "cut up" space differs from the west. |

Is this concept really necessary ?

Of course, a solid argument that can be brought up to us is that such distinction is important to debunk the dolphinarium discourse about captive dolphins and whales being akin to "domestic animals". The idea being to claim, rightfully indeed, that cetaceans aren't "naturally" "made" or "meant" to be captive, and suffer from such setting, and more largely that they aren't spontaneously "loyal" and "naive" to humans, as for a domestic dog. While we believe this to be the truth, the reason why we take such a point of view differs from the mainstream activism in many points.

Classical Ethology can bring us a partial solution to this, as ethological observations well shows tremendous innate behavioral differences between what we call "domestic" and "wild" animals. Basically, artificial selection and genetic drifting with time in artificial environments with less selective pressure shaped domestic animals with a series particular physiological and behavioral traits : droopy ears, neotenic traits, smaller dentition, but also more juvenile behaviors, loss of specialized innate drive toward an increase of more general drives etc. The other point is, of course, our insistence on how innate behaviors are unalterable, and that there isn't such thing as turning a "wild animal" into a "domestic one" through human or captivity influence, and our opposition to the behaviorist credo of an "all learned" and completely alterable animal mind. While the traditional use by our activism of this rhetoric seems to imply a recognition of innate by them, this is far from being the truth, as the traditional activism mostly relies on the usual doxas about animal behavior ; it is more largely less an issue of science or knowledge, which is selective by context, than the fact that the underlying structures of thoughts are generally anthropocentrists and lack self criticism. Worse, this critique of dolphinariums seems less to found itself in any sound science than a fantasy of the "wild animal" expressed by the popular representation of the dolphin, which as we will explore next is double sided.

This point of view, though, has its limits. This is notably because it is oblivious, beyond a correct "scientific use" of the term, of the sociocultural reality behind these terms and their consequences. By 2013, at the pinnacle of my use of classical ethology to "rethink" my activism, I wrote an article for Charlie Hebdo about the dolphinarium industry where I notably wrote that ethology showed us that cetaceans weren't domestic animals, but wild animals, and as such shouldn't be kept in captivity. While I was right in showing how dolphinariums failed in their reasoning, I also was wrong in using such wording, not by a mere problem of respect or political correctness but because I didn't considered at the time all the facets of the word use and its consequences on the perception and relation to cetaceans themselves.

Cetaceans must be though as actively shaping their environment

Like the indigenous people we talked before, we believe necessary to assume that if cetaceans are to be understood as people, then they also should be understood as active shapers of their environment, rather than mere passive harvesters of oceanic resources, and this over social and cultural factors. While it can appear absurd given their lack of technology and the nature of oceanic spaces, several realities should be considered.

The first is that even human population with very primitive technology managed their environments. While this is still an ongoing controversial field of studies, anthropologists are rediscovering clues pointing out toward various indigenous populations actively shaping environments they occupied for tens of thousand of years, such as Australian aborigines with the "fire stick farming" technique. The idea being that many populations changed their environment to suit their need through such techniques as hunting pressure, crop rotation and field burning.

The second one is that this is imaginable from cetaceans in the form of long term hunting pressure (on certain species, under a certain time cycle inside of certain spaces), or in a lesser way through excretions, which are known to impact fish populations. This would come as no surprise, as it could be already be the case in far north human populations such as the Inuits where agriculture and field burning aren't an option.

As such, such conclusions necessarily leads to important political and social implications. One of them is that territories (or "marritories" as I like to name them) inhabited and used by cetaceans must be recognized as owned by them, or in all cases sea resources to be their own as populations, since they are the indirect engineers of these resources. Others are of course that cetaceans must be recognized as owners of their own body ; in all cases, humans, in particular as power-based institutions (whether states, corporations, scientific or conservation institutions etc), should severely limit their power over cetaceans and their seas and have no right to manage or tutelage cetaceans. This, though, isn't synonymous of condemning human cetacean relation ; the last is at the contrary something that the firsts strongly rejects outside of its elitist frame, which keeps a distance with the cetacean by rejecting genuine personal relation or social relation. Part of our job at advocating cetaceans would be indeed to live with them, or providing them with a social reality, particularly liberated, and to reshape our conception of cetacean freedom and our relation to captives : our activism would then have to mutate into a form of protection of oceanic territories from human invasive encroachment, particularly the excessive use of food resources they use.

Of course though, such conclusions are limited, particularly because they still rely on the very problematic conception of "right", itself a corollary of state, which cannot be trusted on these matters ; it is more a social and political aspect rather than a purely isolated ethical one, working on context rather than ontologies and principles as I did in the past. We believe that such an initiative should be collective, from voluntary people outside of any institution. The other problem is that our conception of territory is too "concrete" and "fixed", whereas cetaceans obviously possess a more fluid, open and dynamic conception of territory ; this is already a problem the West faces when dealing with many indigenous or nomadic populations which rely a lot of constant displacement and dispersed resources gathering rather than an agrarian, urbanized lifestyle, which obviously shaped our current conception of "territory" as a delimited places between institutionalized states governing on people.

Cetaceans environment, the so called "sea" or "ocean", is as such not only understood as a "chaotic, dangerous space", but also as a sort of terra nullius which resources can be rightfully harvested at will, whereas their use by cetacean populations - or indeed other lifeforms - aren't to be recognized. In fact, cetaceans are themselves understood as resources, even by the most progressive activists and animal advocates. Humans grant themselves both a right of management, use and ownership of cetaceans, where one can have full disposition of a cetacean body : Scientific and conservation institutions in particular can capture, maintain captive, harass or euthanize at will while their actions are condoned by states worldwide. The general situation of cetaceans all around the globe, free or captives, is akin to colonization, in that whether the cetaceans there will be always a minority of humans in power granting themselves a right of management of ownership of these populations, while their right of ownership are being ignored, their resources depleted, and their exploitation legitimated over a paternalistic rhetoric.

It is as such important in a way to "decolonize" our conception of cetaceans. Questioning not only the nature of the cetacean surroundings and lifestyle but also their representation, a fundamental tool in the legitimacy of their use as objects :

Giving up the fantasies

As we previously saw, as cetaceans continue to be understood as living in "the wilderness", imagined as a sort of "soup" where the cetacean, conceived as living "alone", and "isolated", they are as well to be harvested or managed "for their own good" (sanctuarization of ex captive and some stranded, forced "rehabilitation" based on behaviorism, euthanasia of stranded, tagging and capture in the name of scientific studies and conservation, refusal and penalization of human/cetacean contact worldwide...) by a human scientist elite. This rhetoric is of course pervasive in most people minds, particularly from activists and dolphinariums alike, and is key to understand the legitimation of sanctuaries in particular. Any questioning of sanctuaries as an outcome is generally violently dismissed as "dumping" the dolphin "in the ocean", or illustrated as the cetacean being "alone" "in the middle of the sea" etc. This understanding of liberation is we believe particularly flawed from the beginning, as it understands "liberation" as an "outing" of the "animalized" from a structured social space into a fantasized conception of certain spaces understood as "wild", "chaotic" or "dangerous", which is oblivious of many facts, particularly of cetaceans already possessing social spaces comparable in nature and complexity to human societies. It relies on a series of dubious representations acquired by our western societies and cultures which aren't generally backed on demonstration or experience but on the assumption that the other shares the same fantasized representation ("the wild" "nature" "the middle of the sea"...).

Cetaceans are as such understood in our popular culture under a dichotomy of the "naive, servile dolphin" and the "wild animal" in the same way that the indigenous person was understood in the European imaginary either as the "noble savage" or the "dumb brown man" needing guidance and education. We see from one side a paternalistic iconography invented and extensively used by the dolphinarium industry, which understands the tursiops dolphin in particular as a child-like, smiling creature, living in an idyllic tropical like decorum, head out of the water, begging for attention and here to serve the human in a parody of "friendship" and "love". On the other, an image particularly used by activists of the dolphin which must be "wild and free", with a celebration of the dolphin or whale capacity to "leap", swim or travel in groups for miles in wide oceanic spaces, and its purported keenness to "feast in joy". All these representations of course interact fluidly with each other ; but while they can superficially appear as opposed, they are indeed different expressions of the same underlying anthropocentrist structure of domination.

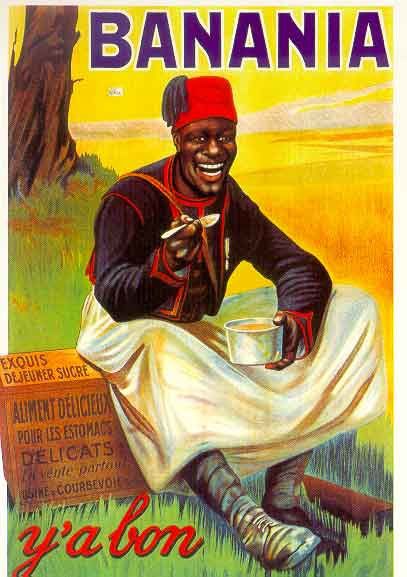

It is impossible not to draw strong parallelisms between these popular representation of cetaceans and "dolphins" in particular in our western popular culture as a tool of legitimation of their exploitation and the way certain categories of human people were depicted in the west to legitimate certain practices, particular indigenous people during colonization or women during the XIXth century. The general representation of the "stupid, smiling, servile dolphin", used by dolphinariums or sanctuaries proponent to legitimate captivity ("the poor dolphin is unfortunately unable to live in the wild anymore, it must live under the care and love of a specialized staff for the rest of its life"), shows strong parallelism with the depiction of indigenous people during European and American colonialism in the XIXth and XXth century, particularly colonial France. The "Banania" mascot is a well known instance of the paternalistic depiction of black people from Africa as naive, child-like, always smiling, and servile people, with the general idea that they are too chaotic to govern themselves and need the forced, external tutoring of European "civilization" to live well.

These fantasies of course tend to work in a fluid way : the dolphinarium industry heavily used the former positive representation as well, as dolphin shows paradoxically rely on these cliches founded on an idealized view of "freedom", with an emphasize on the way dolphins jump or leap in particular.

On the other, we can ever find a third aspect which concentrate on a definitely negative, rejection-based conception of cetaceans as "wild animals". While rarer, it appears at time to notably legitimate certain segregating practices between cetaceans and humans. A typical illustration are marine biologists and conservationists systematically sermonizing people on medias about dolphins being "wild animals" we should "keep a distant with", enforcing contact prohibition worldwide. In this case, the notion of "wild animal" is interpreted in the sense of "savage brute without morals", with an emphasize over rape or murder cases from dolphins - particularly on certain Scottish cases of tursiops allegedly killing babies or porpoises.

In fact, the overfocalisation on rape from dolphins seems to be a recent obsession in our popular culture, widely shared in social medias and "buzz" articles and undoubtedly because it contrasts with their usual positive or naive depictions in our societies. Of course, one cannot but think about the negative conception of indigenous people during colonial time as "cannibals" or "rapists", particularly black men, justified both to excuse their tutelage and the rejection of any higher social or personal recognition of these people ; one can think about Fanon's analysis of the oversexualisation of black men in European culture (Peau Noire, Masque Blanc).

Sources and references :

*J. Baird Callicott, "A critique of and an alternative to the Wilderness idea" (1994)

*William Cronon, "The Trouble with Wilderness; or, getting back to the wrong nature" (1995)